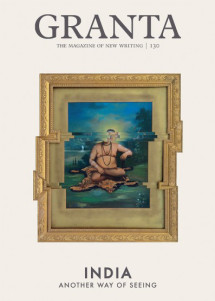

Granta’s issue 130, released in Winter 2015, is the second issue to have been exclusively dedicated to Indian writing in the journal’s history. In the year 1997, Granta experimented with first such issue. It was quite a hit, featuring writings by Anita Desai, R. K. Narayan, V. S. Naipaul, etc. This was the issue in which an excerpt from Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things made its first public appearance. The issue 130 similarly features many known-names of the Indian literary scene.

Granta’s issue 130, released in Winter 2015, is the second issue to have been exclusively dedicated to Indian writing in the journal’s history. In the year 1997, Granta experimented with first such issue. It was quite a hit, featuring writings by Anita Desai, R. K. Narayan, V. S. Naipaul, etc. This was the issue in which an excerpt from Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things made its first public appearance. The issue 130 similarly features many known-names of the Indian literary scene.

Most of the fictional pieces are glaringly open-ended. That could be because these works are excerpts from larger works, and perhaps a reason why they suffer from lack of compactness and impetus. On the other hand, the non-fictional essays, which clearly excites the editor Ian Jack as the promising new phase of the Indian literature, are meticulously researched, poignant, and evocative. My personal favorite is Samanth Subramanian’s “Breach Candy” for its incisive prying open of a discriminatory issue and punchy prose.

One popular theme of this collection seems to be the rising global connections or movements of Indians. The desire to see Indian locales or subjects within an intersectional global context is a fascinating and tempting preoccupation, which many authors in this volume crystallize with their own unique flair. In “Pyre,” an autobiographical piece by Amitava Kumar, a son’s attempt to process the rituals surrounding his mother’s funeral puts him in the position of a stranger, an “outsider.” Kumar, who lives in NYC, sums up his physical distance from his native land this way: “the ironies of our self-discoveries in the mirror of Western knowledge…tugs at the immigrant’s dread that distance will prevent his fulfillment of filial duty.” In Deepti Kapoor’s story “A Double-Income Family,” we get a complex portrait of the conscientious elites of contemporary India who on one hand move to embrace the Western progressive values and acknowledge the legitimacy of their domestic servants as psychosocial beings but can never let go enough to upend the old feudal structure. To illuminate how India’s historical margin is not free of World War II atrocities, Raghu Karnad writes in “The Ghost in the Kimono” of an internment camp in Old Fort in New Delhi for Japanese nationals captured during the process of Britishers’ retreat from British Malay after the Japanese attack. His point: “What were we supposed to make of finding them there in [1942], hidden in the crease between one empire [British Raj] and its successor [India’s Independence]? Nothing, so we remember nothing, except when they come back from the dead to surprise us.” A sardonic reprimand for those who prefer a sanitized and insular version of history. Moving on to Upamanyu Chatterjee’s “Othello Sucks,” we get an unforgiving rendition of the dysfunction that can be contemporary India: how characteristic of Chatterjee! The reader may easily mistake that this story is not happening in New Delhi but some small town in USA; a testament to how clonally Western upper class Indians can be. Playing off of the racial motif surrounding the character Othello, Chatterjee draws a parallel, exposing the unapologetic racial biases prevalent in the day-to-day Indian discourse. Then, Neel Mukherjee provides this detail in his short story: “Then he took his wallet and tried to count the rupee and US dollar nestled together…” Not an incongruous detail considering his story is about an NRI character visiting Agra with his son. But then this detail serves as an apt metaphor for the straddling identities of many upper and middle-class Indians in the twenty-first century.

Of course, there are exceptions to the above theme: Anjali Joseph’s “Shoes,” Arun Kolatkar’s “Sticky Fingers,” and Vinod Kumar Shukla’s poems. In fact, Shukla’s “This year too in the plains” seems to pine for a locale that is spatially drawn closer, that does not get fractured, that does not bleed its citizens to far-off, distant places: “All places should be displaced / And brought near all other places / So that every place is near every other place / And not a single person is displaced / From the village this year.” But then displacement (migration) is the unavoidable fate for many Indians, currently. Be it the exodus from rural to urban India or many leaving the country behind for a future abroad. Granta’s issue is tilted toward an Indian literary experience that is globalized and cosmopolitan.

To denote few examples of how some of the authors in this issue describe India from their viewpoint in their unique style:

A security guard sits at a desk in one corner, watching over the children at play. Not that anybody expects grievous breaches of peace in a kiddies’ park, but it is pro forma today in India to strew security guards thickly through any establishment, protecting nothing except the fancy that the premises are worth protecting. – “Breach Candy” by Samanth Subramanian

They [the parents] prefer to bicker in front of the children, firmly believing that hearing the verbal duels of their parents helps in their mental development, giving them metaphors and turns of phrases that they would otherwise have taken a decade to make their own. – “Othello Sucks” by Upamanyu Chatterjee

The walls of the Old Fort, called the Purana Qila in Urdu, are not the oldest in Delhi, not by many centuries. Underneath them, however, the past runs deepest. Here is some of the most saturated archaeological terrain in India, cluttered with ceramics, stone, bone and crystal, toys, dice, gods and potsherds, mineral memoranda from every human age. They form an aquifer of fluid pasts, to be left sunken or pumped up according to modern convenience. – “The Ghost in the Kimono” by Raghu Karnad

But the chappals will be his constant companions. He’ll spend more time with them than with his wife. One side of the sole may wear out more, depending on how he walks, so that you could pick up his chappals and observe that he leans a little into his center, or a little towards the world. – “Shoes” by Anjali Joseph

Onlookers peer out from the margins, their faces inscrutable amid all the posing and scuffling, shouting and jostling. In Punjab, a pink-cheeked boy, standing under a sign that reads SHOE STORE, stares at Chauhan astride a motorcycle festooned with the national flag and a garlanded plastic bust of pre-independence revolutionary Bhagat Singh. – “Love Jihad” by Aman Sethi